On the past and future of HCI

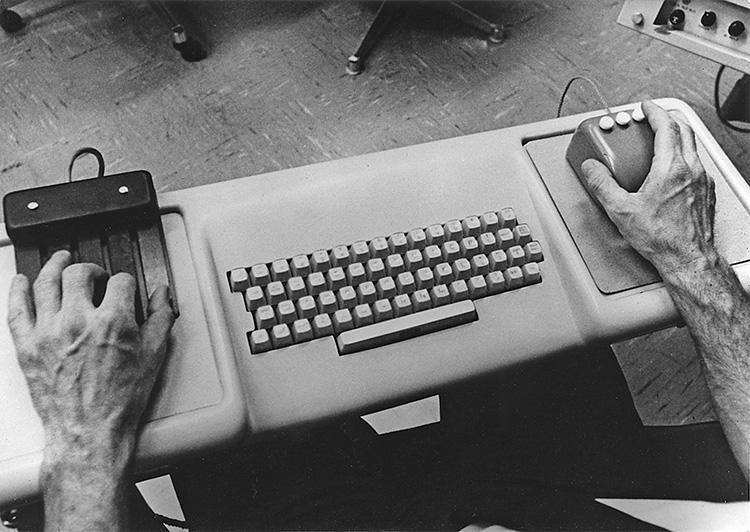

In 1968, Douglas Engelbart stunned the computing world The Mother of All Demos, introducing a visionary suite of interaction tools – including what he called an "X-Y position indicator for a display system".

“When you were interacting considerably with the screen, you needed some sort of device to select objects on the screen, to tell the computer that you wanted to do something with them” - Douglas C.Engelbart

Today, we know it as the mouse.

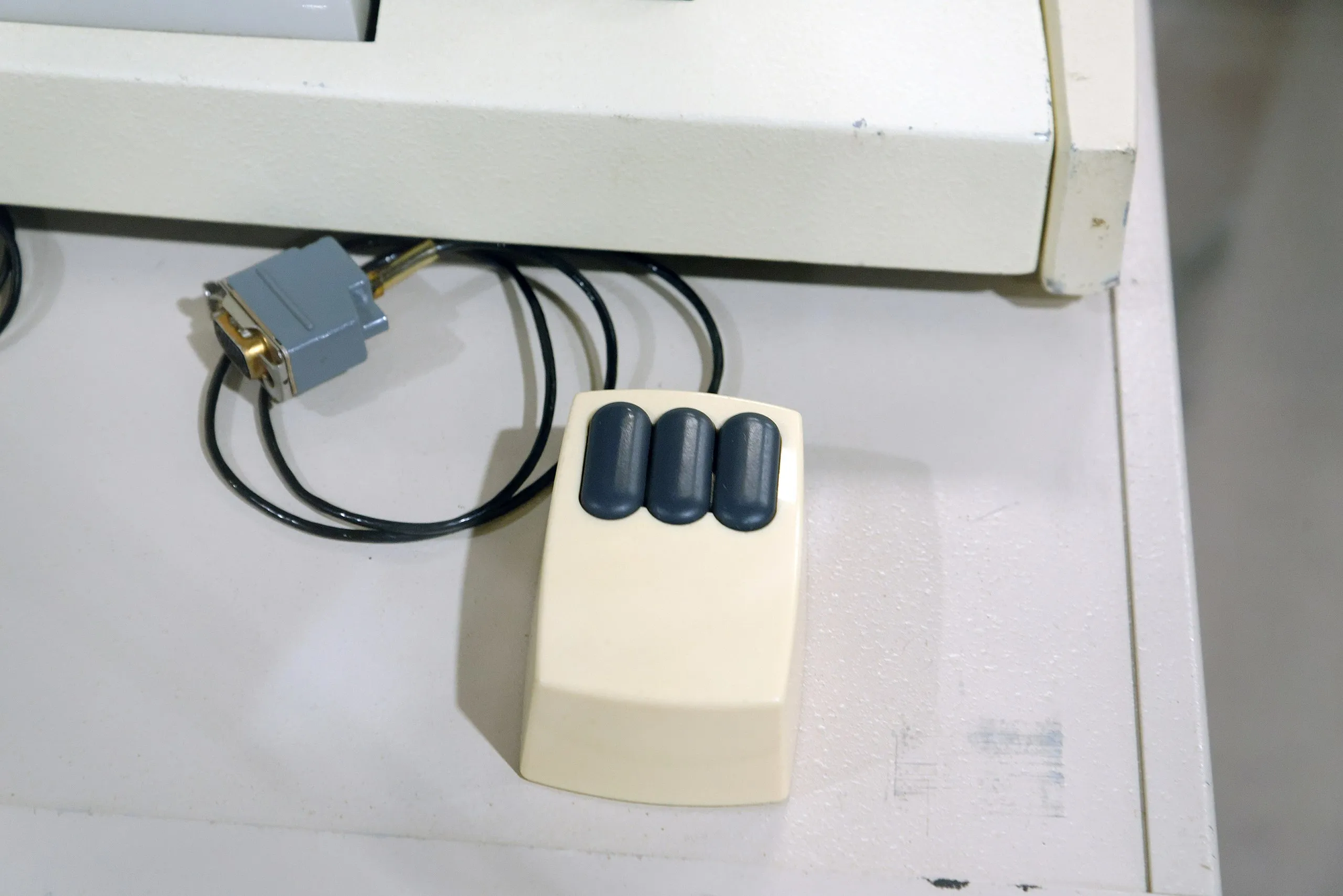

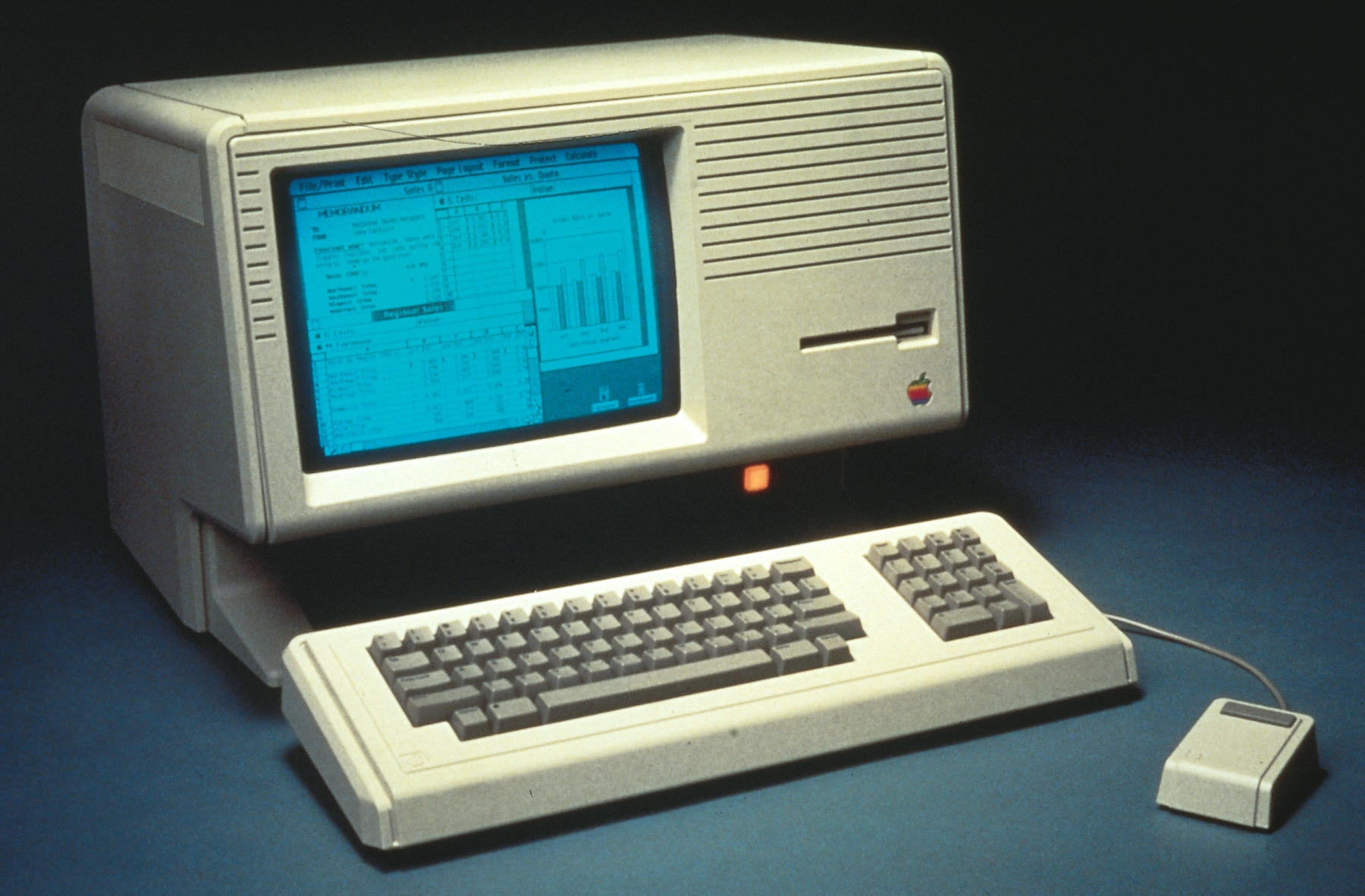

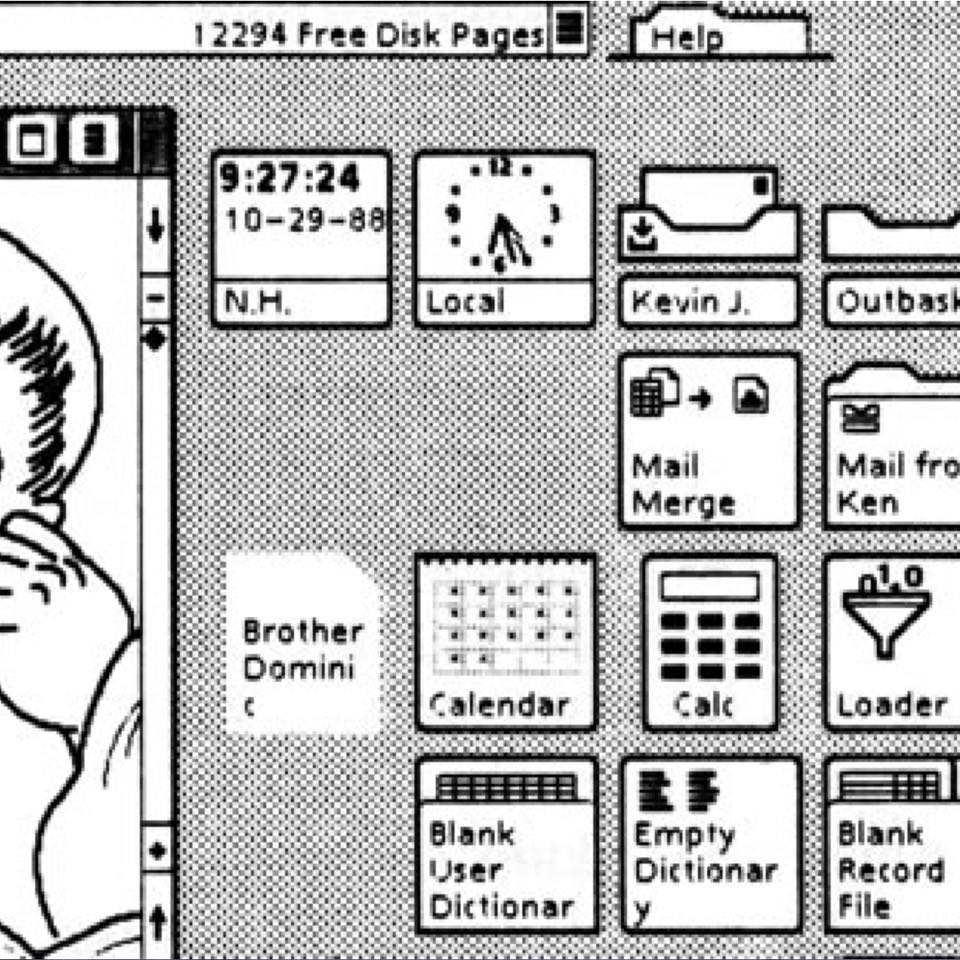

Yet, this revolutionary idea took over a decade to leave the lab. The Xerox Alto, introduced in 1973, was the first graphical user interface and mouse pairing, but it was restricted to research use. Only in the 1980s, with Apple's Lisa and later the Macintosh, did the mouse begin to reach the hands of ordinary users.

It took 20 years, for such a revolutionary idea, to go from demo to the hands of consumers. Many more years for it to take over the world, as the most successful device for human computer interaction.

The Frustration That Sparked a Discipline

By the late 1970s, the computing landscape was transforming rapidly. Microprocessors enabled increasingly powerful machines, but most interfaces remained cryptic – made by engineers, for engineers. Features were abundant, yet users were confused.

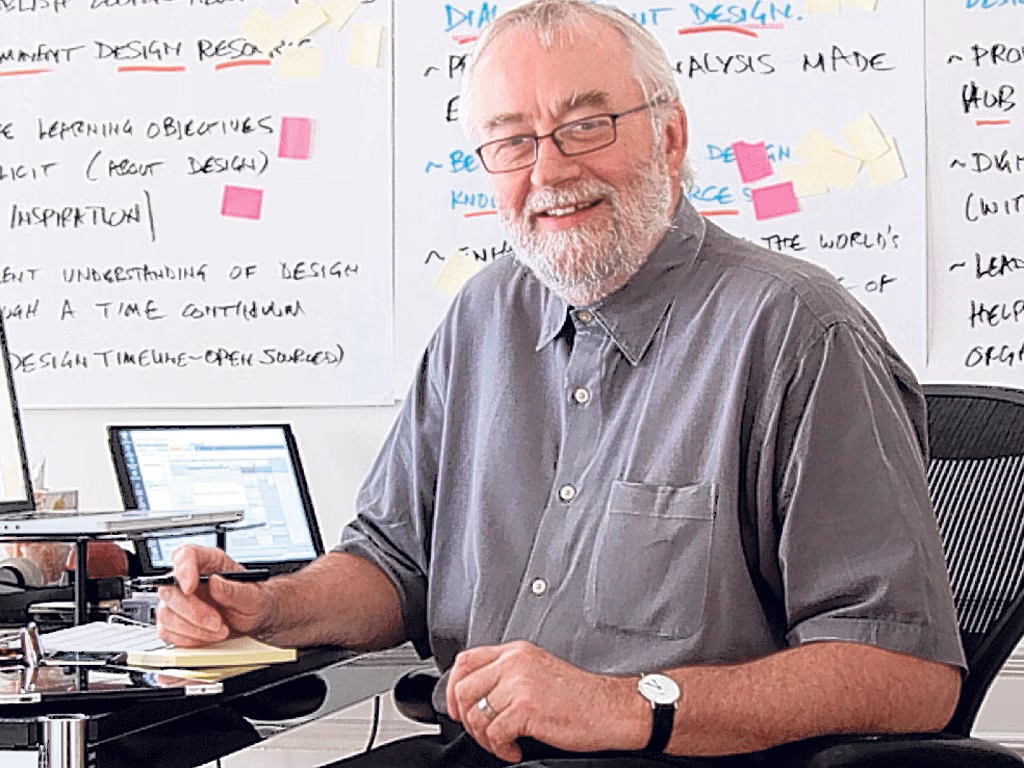

It was in this context that designer Bill Moggridge recognized a critical gap: we had learned how to build powerful systems, but not how to design interactions. As the designer of the GRiD Compass – the first commercially available laptop, Moggridge faced a paradox. The hardware was cutting-edge, used even by Nasa aboard the Space Shuttle. Yet, the software interfaces remained primitive, difficult to use without training or manuals.

One device crystallized his concern: the radio watch. Developed in the early 1980s, the watch combined FM radio with a digital alarm. Technologically impressive, it was also maddeningly complex. Something as simple as setting the alarm could require dozens of button presses, a process detailed in a manual thicker than the watch itself.

"It was designed around the chip, not the human," Moggridge later observed.

From this realization came a new design philosophy: one focused not on the internal logic of machines, but on the needs, perceptions, and behaviors of users. Moggridge initially called this approach "soft-face", a playful reference to "software interface", in which the focus was mainly on GUIs of early computers. The term soon evolved into something more enduring: Interaction Design.

A Familiar Problem in a New Form

Today, the frontier of computing has shifted again: from desktops to AI systems, wearables, smart environments, and ubiquitous sensors. While the technology has changed, the core tension remains: capability is growing faster than comprehensibility.

Consider AI-powered tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, or smart assistants. While these systems can generate natural-sounding responses, art, or summaries, users often struggle to understand how or why the system behaves the way it does. Prompt engineering has become an informal skill, yet the interfaces have not matured to support transparency, feedback, or trust.

"Chatting" with LLM feels like using an 80s computer terminal. The GUI hasn't been invented, yet but imo some properties of it can start to be predicted.

— Andrej Karpathy (@karpathy) May 1, 2025

1 it will be visual (like GUIs of the past) because vision (pictures, charts, animations, not so much reading) is the 10-lane… pic.twitter.com/PnUnHxvaMo

We are repeating a familiar pattern: technological breakthroughs without corresponding advances in human-centered design. Just like the radio watch, today's intelligent systems often prioritize functionality over clarity.

There needs to exist a new paradigm of design, built around new technology, and a new class of designers who understand both human psychology and the technical systems they interact with.

Designing for the Unknown

Why do we organize software in windows and icons? Why does clicking a picture launch an action?

These conventions feel natural now, but they were once radical experiments aimed to answer questions that no one had asked before.

The real insight is this: good interfaces are not found, they are invented. They emerge from rigorous research, asking questions like: what mental model does this build, how many bits per second can it deliver,...

"Good interfaces are not found; they are invented" - Binh Pham

To design the next generation of interactions, we must again go through the same process, methodically, iteratively, and extremely. This calls for a new kind of designers and engineers, who can bridge the logic of machines with the chaos of people.